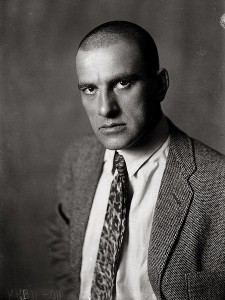

Poems by Vladimir Mayakovsky

Mayakovsky’s father was an impoverished nobleman who worked as a senior forester in the Caucasus. As a boy, Mayakovsky would climb into a huge clay wine vat and read poetry aloud, trying to swell the power of his voice with the vat’s resonance. Mayakovsky was not only Mayakovsky, but the powerful echo of his own voice: oratorical intonation was not just his style, but his very character.

While imprisoned in Butyrka prison in Moscow in 1909, when he was only sixteen, Mayakovsky became engrossed in the Bible, one of the few books available to him there, and his early thunderous verses are strewn with biblical metaphors whimsically tied to boyish blasphemies. He intuitively perceived that “the street will convulse, tongueless, with no means to cry out and speak”; and so he gave the word to the street and thus revolutionized Russian poetry. His brilliant poems “A Cloud in Trousers” and “Flute and Spine” towered above the verses of his poetic milieu, just as the majestic peaks of his native Caucasus towered above the little houses that clung to their sides. While calling for the ejection of Pushkin and other gods of Russian poetry from the “steamship of modernity,” Mayakovsky actually continued to write in the classical tradition. With his companions Mayakovsky founded the Futurist movement, whose early collection was called, significantly, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1912). Gorky was right when he remarked that while Futurism perhaps did not exist, a great poet did: Mayakovsky.

There was no question for Mayakovsky about whether to accept the October Revolution. He was himself the revolution, with all its power, its excesses, its epic vulgarity and even brutality, its errors and tragedies. Mayakovsky’s revolutionary zeal is evident in that this great love-lyric poet committed his verse to the service of ideological limericks, to the advertising billboards of politics. In this zeal, however, lay his tragedy, for he consciously stood “on the throat of his own song,” a position he once underscored brilliantly: “I want to be understood by my native land, but I won’t be understood — Alas! I will pass through my native land like slanting rain.”

His despondency in personal affairs as much as his disillusionment with politics led him to shoot himself with a revolver he had used as a prop in a movie twelve years earlier. Because he was both revered and reviled, his death held profound though various meaning for everyone. Tens of thousands of people attended his funeral. Mayakovsky was canonized by Stalin, who said about him: “Mayakovsky was and remains the best and most talented poet of our time. Indifference to his poetry is a crime.” This was, in Pasternak’s view, Mayakovsky’s second death. But he died only as a political poet; as a great poet of love and loneliness he survived.

Vladimir Mayakovsky

2. Левый марш

4. Товарищу Нетте, пароходу и человеку

6. Красавицы

4. То Comrade Nette, the Man and The Ship

5. Build the Material Base!

Стихи о советском паспорте

Vladimir Mayakovsky

The Poem of the Soviet Passport

(Translated from the Russian

По длинному фронту

как будто берут чаевые,

снесет задаром вам.

С каким наслажденьем

исхлестан и распят

что в руках у меня

A courteous official

The maze of compartments

They hand in passports,

my red-skinned pass.

arouse an obliging smile

are treated as mud.

with special regard.

with an exorbitant honor,

They take his passport

The Polish passport

Like a sheep might stare

at a Christmas tree:

Where does it come from,

this silly and queer

to use their brains,

passports from Danes

And other sorts of

as if he had burnt

It’s my red passport

or those sorts of things,

As if it were a snake

with dozens of stings.

I’d be fiercely slashed and hanged

I have got in my hand

I’d root out bureaucracy

from my loose pantaloons,

Read it and envy me:

ЛЕВЫЙ МАРШ

Vladimir Mayakovsky

LEFT MARCH

(Translated from the Russian

Разворачивайтесь в марше!

Довольно жить законом,

данным Адамом и Евой.

Клячу истории загоним.

у броненосцев на рейде

ступлены острые кили?!

вздымает британский лев вой.

Коммуне не быть покоренной.

солнечный край непочатый.

шаг миллионов печатай!

Пусть бандой окружат нанятой,

России не быть под Антантой.

Глаз ли померкнет орлий?

В старое станем ли пятиться?

Грудью вперед бравой!

Флагами небо оклеивай!

Away with a talk-show.

Silence, you speakers!

Down with the law which for us

Adam and Eve have left.

We’ll ruin the jade of the past.

Sail away! Overseas!

Or is there anything wrong

of your battleships?

the vigorous British Lion

Keep howling, frenzied and chafed.

The commune shall not resign.

o’er the hills of sorrow

There’s a land of the rising sun.

for the sea of horror,

May them gang up against us,

To all their threats we»ll be deaf,

The Entente shall never suppress us.

Can the eagle ever get blind?

Can they make us swing off the road?

your proletarian hand

tight on the world’s throat!

Deck out the sky with drape!

Who’s marching out of step?

Vladimir Mayakovsky

THE PARISIAN WOMAN

(Translated from the Russian

Вы себе представляете

Бросьте представлять себе!

молода или стара она,

разулыбив облупленный рот,

за пятьдесят сантимов

над мадмуазелью недоумевая,

Выглядите Вы туберкулезно и вяло,

Чулки шерстяные. Почему не шелка?

Почему не шлют Вам пармских фиалок

of a Parisian woman?

with a gemmed hand?

The Parisian I know

is nothing of the kind.

whether she is old

In a gloss of finery

at the toilet of a restaurant

A little restaurant

After having a drop

one may have a desire

To refresh oneself

is to help with a towel,

And she is a conjurer

You sit at the mirror

Watching your pimples

Will powder your face

and put some perfume,

and give you a towel.

To please the gluttons

In the somber lavatory

For fifty centimes!

for every good turn).

I go to the washstand

Inhaling the marvel

of perfumery smell,

Her wretched plainness

to the mademoiselle:

is far from being pleasing.

Why should you spent your life

I must have thought

Your manners are languid

and you look unhealthy.

The stockings you wear

aren’t silk but plain.

the moneyed messieurs

With bunches of violets

The air being rent

By a loud street noise

That was the noise

of the carnival merriment

Of young Parisians

for a rigorous poem like this,

For having mentioned

for a woman to live

not to sell her soul.

Товарищу Нетте,

пароходу и человеку

Vladimir Mayakovsky

То Comrade Nette,

the Man and The Ship

(Translated from the Russian

Я недаром вздрогнул. He загробный вздор.

В порт, горящий как расплавленное лето,

разворачивался и входил товарищ «Теодор

В блюдечках-очках спасательных кругов.

— Здравствуй, Нетте! Как я рад, что ты живой

дымной жизнью труб, канатов и крюков.

Подойди сюда! Тебе не мелко?

Медлил ты. Захрапывали сони.

Глаз кося в печати сургуча,

напролет болтал о Ромке Якобсоне

и смешно потел, стихи уча.

Засыпал к утру. Курок аж палец свел.

Думал ли, что через год всего

Залегла, просторы надвое прорвав.

Будто навек за собой из битвы коридоровой

тянешь след героя, светел и кровав.

В коммунизм из книжки верят средне.

«Мало ли что можно в книжке намолоть!»

и покажет коммунизма естество и плоть.

Мы живем, зажатые железной клятвой.

Мы идем сквозь револьверный лай,

чтобы, умирая, воплотиться

в пароходы, в строчки и в другие долгие дела.

Мне бы жить и жить, сквозь годы мчась.

встретить я хочу мой смертный час

I startled. Then I saw that it was not a dream.

Nor was it the fancy of a poet.

The «Theodor Nette» turned about to steam

I have recognized him. He arrived

Wearing round spectacles of safety buoys.

Hello, Nette! I’m so glad that you’re alive,

A smoky life of funnels, hooks and coils.

Now come here. How’s everything?

You must have traveled, boiling, very far.

You remember, when a human being,

Having tea with me in a sleeping car?

People snored while you sat up till morn.

Squinting at the sealing-wax with half closed eyes.

You would talk about Rommie Yakobson

And amuse yourself by learning rhymes.

You’d fall asleep at dawn, revolver at the ready.

Was there anybody going to pry?

Could I think that in a year’s time already

Big and bright is the moon that shines in your rear,

The vast is divided in two by its light.

As if you were dragging the trace of a hero

From the scene of a severe naval fight.

We don’t believe in communism from the books we read

There is a lot of rubbish in them as a rule.

But this is something that turns all «fibs» to real

And reveals the gist of the idea to the full.

We are living bound by an iron oath,

And we might as well be hanged and crushed

For we want this world to be a common earth

We have blood, not water flowing in our body.

We are marching through the pistol din

So that consequently we might be embodied

In a ship, a poem or some other lasting thing.

I would go on living following my bent.

And the only wish that I would dare venture

Is that I could meet my latter end

Just like comrade Nette met his last adventure.

ДАЁШЬ МАТЕРИАЛЬНУЮ БАЗУ!

BUILD THE MATERIAL BASE!

(Translated from the Russian

Пусть ропщут поэты,

обязательных при социализме.

в грязи побираться.

А вместо этого лифта

Пусть ропщут поэты,

Let poets grumble,

and splutter playing pipers,

And let them curl their lips

What socialism can»t do without.

«The floor I live on

I want, dear comrades,

I»m not a thrush for you,

a whole mass.

I want to rise

high up in life, indeed,

I come from lowest class,

Comrades, I»d rather live

high up above,

Prominence.

We are neither horses,

comrades,

nor children, really,

Riding a horse

with a lift instead.

they»d better wait!

On the white wall

In scrawls: » The lift

WON»T

a lot of thing

are just disgusting.

Say, primus stoves!

Make way to gas!

And after work

Let’s build

material base,

taking a chance,

for brand-new

socialist relations».

Let poets grumble,

and splutter playing pipers,

And let them curl their lips

(Раздумье на открытии Grand Opera )

( Meditation on the opening of Opera House)

Translated from the Russian

Slipped into dinner jacket,

perfectly shaved,

I am

During the interval

a lot of beauties. Great!

My disposition melted,

are Houbigant rosy.

the blue of the eyes.

the blossom of salmon,

Dropping

from height,

the trains

for you it»s a bore.

As she turns her rear

you»ll see diamonds in her ear.

As she playfully stirs,

You won»t breathe, I bet.

and crêpe de Chine.

is crêpe Georgette,

you get.

But it would be best

if, along with the dress,

(Translated from the Russian

Ешь ананасы, рябчиков жуй,

Eat grouse, chew pineapples, bourgeois,

You are coming to your final day, you are.

ДАЁШЬ МАТЕРИАЛЬНУЮ БАЗУ!

BUILD THE MATERIAL BASE!

(Translated from the Russian

Пусть ропщут поэты,

обязательных при социализме.

в грязи побираться.

А вместо этого лифта

Пусть ропщут поэты,

Let poets grumble,

and splutter playing pipers,

And let them curl their lips

What socialism can»t do without.

«The floor I live on

I want, dear comrades,

I»m not a thrush for you,

a whole mass.

I want to rise

high up in life, indeed,

I come from lowest class,

Comrades, I»d rather live

high up above,

right by the side of

We are neither horses,

comrades,

nor children, really,

Riding a horse

with a lift instead.

they»d better wait!

On the white wall

In scrawls: » The lift

WON»T

a lot of thing

are just disgusting.

Say, primus stoves!

Make way to gas!

And after work

Let’s build

material base,

taking a chance,

for brand-new

socialist relations».

Let poets grumble,

and splutter playing pipers,

And let them curl their lips

(Раздумье на открытии Grand Opera )

( Meditation on the opening of Opera House)

Translated from the Russian

Slipped into dinner jacket,

perfectly shaved,

I am

During the interval

a lot of beauties. Great!

My disposition melted,

are Houbigant rosy.

the blue of the eyes,

the blossom of salmon,

Dropping

from height,

the trains

for you it»s a bore.

As she turns her rear

you»ll see diamonds in her ear.

As she playfully stirs,

You won»t breathe, I bet.

dressed up in faille

and crêpe de Chine.

is crêpe Georgette.

Tania-Soleil Journal

Параллельные переводы. Фоторепортажи. Статьи об изучении иностранных языков.

Смерть поэта. Стихи В. Маяковского на английском языке

| Всем В том, что умираю, не вините никого и, пожалуйста, не сплетничайте. Покойник этого ужасно не любил. Мама, сестры и товарищи, простите — это не способ (другим не советую), но у меня выходов нет. Лиля — люби меня. Товарищ правительство, моя семья это Лиля Брик, мама, сестры и Вероника Витольдовна Полонская. Если ты устроишь им сносную жизнь — спасибо. Начатые стихи отдайте Брикам, они разберутся. Как говорят: «инцидент исперчен», любовная лодка разбилась о быт. Я с жизнью в расчете и не к чему перечень взаимных болей, бед и обид. Счастливо оставаться. Владимир Маяковский 12/IV 30 г. |

14 апреля 1930 г. «Красная газета» сообщила:

Об этой трагедии Марина Цветаева однажды написала:

«Двенадцать лет подряд человек-Маяковский убивал в себе Маяковского-поэта, на тринадцатый поэт встал и человека убил».

Два стихотворения Владимира Маяковского на английском языке

О, если б я нищ был!

Как миллиардер!

Что деньги душе?

Ненасытный вор в ней.

Моих желаний разнузданной орде

не хватит золота всех Калифорний.

Если б быть мне крсноязычным,

как Данте

или Петрарка!

Душу к одной зажечь!

Стихами велеть истлеть ей!

И слова

и любовь моя —

триумфальная арка:

пышно,

бесследно пройдут сквозь нее

любовницы всех столетий.

О, если б был я

тихий,

как гром, —

ныл бы,

дрожью объял бы земли одряхлевший скит.

Я если всей его мощью

выреву голос огромный, —

кометы заломят горящие руки,

бросаясь вниз с тоски.

Я бы глаз лучами грыз ночи —

о, если б был я

тусклый, как солце!

Очень мне надо

сияньем моим поить

земли отощавшее лонце!

Пройду,

любовищу мою волоча.

В какой ночи’

бредово’й,

недужной

какими Голиафами я зача’т —

такой большой

и такой ненужный?

1916

Ponderous. The chimes of a clock.

«Render unto Ceasar… render unto God…»

But where’s

someone like me to dock?

Where to find waiting — a lair?

Were I

like the ocean of ocean little,

on the tiptoes of waves I’d rise,

I’d strain, a tide, to caress the moon.

Where to find someone to love

of my size,

the sky too small for her to fit in?

Were I poor

as a multimillionaire,

it’d still be tough.

What’s money for the soul? —

Theif insatiable.

The gold

of all Californias isn’t enough

for my desires’ riotous horde.

I wish I were tongue-tied,

like Dante

or Petrarch,

able to fire a woman’s heart,

reduce it to ashes with verse-filled pages!

My words

and my love

form a triumphal arch:

through it in all their splendour,

leaving no trace,will pass

the inamoratas of all the ages.

Were I

As quiet as thunder,

how I’d wail and whine!

One groan of mine

would start world’s crumbling cloister shivering.

And if

I’d end up by roaring

with all of its power of lungs and more —

the comets, distressed, would wring their hands

and from the sky’s roof leap in fever.

If I were dim as the sun,

night I’d drill

with the rays of my eyes,

and also

all by my lonesome,

radiant self

build up the earth’s shivering bosom.

On I’ll pass,

dragging my huge love behind me.

On what feverish night, deliria-ridden,

by what Goliaths was I begot —

I, so big

and so no one needen?

и вдруг разревелась

так по детски,

что барабан не выдержал:

«Хорошо, хорошо, хорошо!»

А сам устал,

не дослушал скрипкиной речи,

шмыгнул на горящий Кузнецкий

и ушел.

Оркестр чужо смотрел, как

выплакивалась скрипка

без слов,

без такта,

и только где-то

глупая тарелка

вылязгивала:

«Что это?»

«Как это?»

А когда геликон —

меднорожий,

потный,

крикнул:

«Дура,

плакса,

вытри!»-

я встал,

шатаясь полез через ноты,

сгибающиеся под ужасом пюпитры,

зачем-то крикнул:

«Боже!»

Бросился на деревянную шею:

«Знаете что, скрипка?

Мы ужасно похожи:

Я вот тоже

ору —

а доказать ничего не умею!»

Музыканты смеются:

«Влип как!

Пришел к деревянной невесте!

Голова!»

А мне — наплевать!

Я — хороший.

«Знаете что, скрипка?

Давайте —

будем жить вместе!

А?»

1914

then suddenly burst into sobs,

so child-like

that the drum couldn’t stand it:

«All right, all right, all right!»

But then he got tired,

couldn’t wait till the violin ended,

slipped out on the burning Kuznetsky

and took flight.

The orchestra looked on, chilly,

while the violin wept itself out

without reason

or rhyme,

and only somewhere,

a cymbal, silly,

kept clashing:

«What is it,

what’s all the racket about?»

And when the helicon,

brass-faced,

sweaty,

hollared:

«Crazy!

Crybaby!

Be still!»

I staggered,

on to my feet getting,

and lumbered over the horror-stuck music stands,

yelling,

«Good God»

why, I myself couldn’t tell;

then dashed, my arms round the wooden neck to fling:

«You know what, violin,

we’re awfully alike;

I too

always yell,

but can’t prove a thing!»

The musicains commented,

contemptuously smiling:

«Look at him-

come to his wooden-bride-

tee-hee!»

But I don’t care-

I’m a good guy-

«You know, what, violin,

let’s live together,

eh?».

Посмертная записка поэта,

написанная им за два дня до самоубийства